ENGL 1200 Interpretation of Literature:

Fall 2024: Shakespeare: Until the Last Syllable of Recorded Time

In 1623, the poet Ben Jonson adorned the first folio edition of the collected works of William Shakespeare with a poem expressing his admiration for “The Bard” which declares that “He was not of an age but for all time!” The 401 years since have proven Jonson to be as much prophet as poet, with adaptations of Shakespearean stories continuing to be churned out on a consistent basis to this day. Hamlet, for instance, has recently been reinvented and repackaged for the screen as a family tragedy about Vikings (The Northman, 2022), motorcycle gangs (Sons of Anarchy, 2008), and even animated lions (The Lion King, 1994). In 2018 alone King Lear inspired not one, but two, television shows about the sort of fathers who cultivate “daddy issues” in their children: Succession and Yellowstone. And, one cannot toss a stone in a bookstore without hitting a book that borrows its title, if not its content, from Shakespeare, such as The Fault in our Stars, Infinite Jest, and The Sound and the Fury.

In this class we will strive to uncover the reasons for William Shakespeare’s enduring literary legacy. We will begin by deconstructing that legacy, and separating the man from the mythology, with the aid of Maggie O’Farrell’s historical novel, Hamnet. A sequence of Shakespearean sonnets, paired with contemporary poems that echo Shakespeare’s sentiments and sympathies, will allow us to consider the purpose of poetry through the ages. We will toil and trouble over the tragedy of Macbeth and then reconsider the play through the eyes of Akira Kurosawa, one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, with his adaptation of the play: Throne of Blood. As the weather begins to chill, we will turn towards The Winter’s Tale and follow the story from stage to page by reading Jeanette Winterson’s novel treatment of the play, The Gap of Time. The course will conclude with a series of non-fiction essays which reveal the complications of Shakespeare’s legacy today and a rousing debate over the significance, or the lack thereof, of Shakespeare for this and future generations.

Summer 2024: Summer in the City of Literature

With all due respect to the cornfields of Nebraska and the cafes of Brooklyn, it is a truth universally acknowledged that Iowa grows two crops better than anywhere else: corn and writers. The University of Iowa revolutionized the way writing is taught by founding the first creative writing program at the collegiate level in 1936. In the years since, TheWriter’s Workshop has fostered the development of countless prominent authors, and in 1967 Paul and Hualing Nieh Engle took Iowa writing global by establishing the International Writing Program, bringing over 1600 writers from 160 different countries to Iowa City. The success of these programs, alongside a bustling undergraduate major and numerous community writing groups, resulted in the United Nations Educational,Scientific, and Cultural Organization naming Iowa City a UNESCO City of Literature in 2008—the first city in the United States to earn the coveted distinction.

In this course we will explore Iowa City’s rich literary tradition, figuratively by reading

the works of authors who have called the University of Iowa home and literally by taking excursions to literary landmarks around the city. In the classroom we will form our own community of readers and writers through the shared experience of close-reading the same texts together, while also centering your own unique perspective as a reader.

Spring 2024 and Spring 2023: Reading in Community

What goes into making a text? How do historical and cultural contexts create conditions for writing, and how does that affect what does or does not make it into the margins? As readers, how do the temporal, geographical, and bodily spaces we inhabit shape our engagement with other texts? Literature does not exist within a vacuum but is instead a product of the vibrant communities in which it is created. This course will explore community as a literary theme, as an approach to reading, writing, and discussing literature, and also as a foundation for participation in Service Learning. Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran, will guide us in interrogating how different communities read and interpret literature in vastly different ways. We will read several texts written by members of the University of Iowa’s storied literary community, and we will ourselves become members of the vibrant literary community of Iowa City—one of only two cities in the United States that has been designated as a UNESCO City of Literature.

In the classroom we will form our own community of readers through the shared experience of close-reading the same texts together, while also centering your own unique perspective as a reader. We will discuss how texts relate to your own experiences and expectations, as well as to their historical, cultural, and literary contexts. Discussion topics will include race, sexuality, alienation, dehumanization, family, love, and the usefulness of literature in the modern world.

Furthermore, we will explore what it means to be a part of a community by becoming active citizens of Iowa City and engaging with its artistic community. This section is designated as a Service Learning section of General Education Literature. This will require students enrolled to participate, on several Fridays throughout the semester, in reading one-on-one with students at a local elementary school and the opportunity to participate in storytelling partnerships with young readers, enhancing their reading skills and your own.

Fall 2023: Getting Medieval in the Midwest

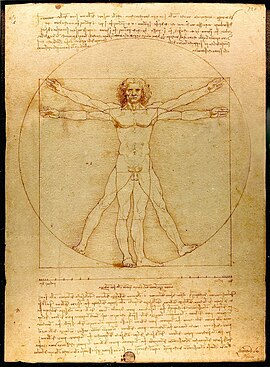

The word “medieval” has been used as a slur for as long as it’s been a word. However, the Middle Ages was more than just a time of superstitious oafs rotating crops and going on Crusade. It is a thousand years of humanity—filled with stories of love and passion, ingenuity, and cooperation, and rich with diverse complex peoples living their best, human, lives. The Middle Ages are also a period rife with massive social inequalities, persecution, and oppression—a time in which plague, pestilence, famine, and war feature in the Sunday sermon precisely because they are common features in everyday lives—lives that may not be as different from you own as you might initially think.

From movies like The Lord of the Rings and A24’s The Green Knight , to television shows such as Vikings and Game of Thrones, and video games like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim and The Witcher, fantastical representations of the Middle Ages have become increasingly popular in the twenty first century. This class will explore why we, as a society, remain so interested in all things medieval and interrogate what we can learn about ourselves by examining the past. In this course, we will examine how the medieval period proves William Faulkner’s assertion that “The Past is never dead. It’s not even past,” to be true. We will visit the University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections and Archives to handle actual medieval books, and we will read medieval masterworks, such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales to provide a foundation for discussing how issues of gender, sexuality, religion, class, and emotion compare and contrast with their conceptions in contemporary society. We will discuss how canonical authors such as William Shakespeare and Alfred, Lord Tennyson drew inspiration from medieval events and reimagined medieval texts to fit their own cultural contexts. We will question how and why contemporary authors and poets, such as Donika Kelly and Nobel laureate Kazuo Ishiguro, have incorporated “the medieval” into their modern fiction and poetry. And, finally, we will develop a community-based practice of reading and annotation which mimics the practices of medieval intellectual communities.

Fall 2022: Bodies on the Page and Stage

The 17th century poet John Milton wrote that “books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them.” This course explores literature as a living document, a guide to our past and our present moment. How have writers used different forms to think differently about our relation to others, our history, our community, and our obligations?

In this course we will interrogate what it means to be “human” by examining the depictions of bodies in literature. We will question notions of bodily autonomy and analyze institutions and systems which exhibit control over bodies. Over the course of the semester we will chart our ever-evolving understanding of the body from the Middle Ages to the present day—while closely addressing questions of sensory perception, technology, language, maternal bodies, gendered and racialized bodies, and representations of aging.

Fall 2021 and Spring 2022: Gods and Monsters

In this course, we will interrogate what it means to be “human” by taking the seemingly

paradoxical approach of examining the inhuman, the supernatural, and the monstrous present in various forms of literature. From ancient mythology to modern Superhero films, the human experience has often been portrayed through our interactions with beings who do not fit into the decidedly restrictive category of “human.” Gods, monsters, devils, and magical creatures will be making regular appearances in our readings, and, over the course of the semester, we will attempt to figure out why that is and what their presence in literature tells us about ourselves and our experiences

Rhetoric 1030:

Spring 2021: Choose your own Rhetorical Adventure

“It is our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.”

― Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

Life is a constant series of making choices, and those choices—from ordering food at a drive-thru to voting—have consequences. The choice to order fast food may result in indigestion, while the choice of a political candidate may lead to a different sort of discomfort altogether. Nevertheless, these choices we make have been influenced by the usage of rhetoric. To further this focus on choice, I will be asking you to help me choose the texts we analyze and discuss in this class. We will vote on the topics we are most interested in as a class. There will be two readings/viewings associated with the chosen topics every week. For the first text of the week I will curate a list of possible texts, and the class will choose via vote. I will choose the second text of the week myself. There will also be numerous skills-based readings along the way as well/

In this class we will work together to cultivate the skills necessary for engaged participation in both Academic and Civic environments—and to make the best possible choices we can.. These skills include thinking critically, reading critically, research, writing, listening, and speaking. Particular focus will be given to the process of crafting effective and informed arguments, as well as methods for articulating said arguments through various mediums. The goal of this class is to provide a foundation for your academic career—a foundation which you will build upon with every future class taken at the University of Iowa.

Fall 2019,Fall 2020, Spring 2020 The Rhetoric of Resistance and Revolution

“The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” -Albert Camus

This section will examine the rhetoric of resistance and revolution. Throughout the course of this class, we will be engaging texts which sparked rebellions

and incited revolutions of all sorts. We will also rhetorically analyze what it means when

the words “rebellion” and “revolution”—as well as their derivatives, “rebel” and

“revolutionary”—are applied in disparate contexts such as music, art, and fashion.

In this class we will work together to cultivate the skills necessary for engaged

participation in both Academic and Civic environments. These skills include thinking

critically, reading critically, research, writing, listening, and speaking. Particular focus

will be given to the process of crafting effective and informed arguments, as well as

methods for articulating said arguments through various mediums. The goal of this class is to provide a foundation for your academic career—a foundation which you will build upon with every future class taken at the University of Iowa.